Mémorial de l’abolition de l’esclavage – Nantes

For some time before the Memorial to the Abolition of the Slave Trade came into being there was little appetite in Nantes for drawing people’s attention to the city’s dark history. An application, for example, to mark the end of slavery with the public display of a plaque, was rejected by officials.

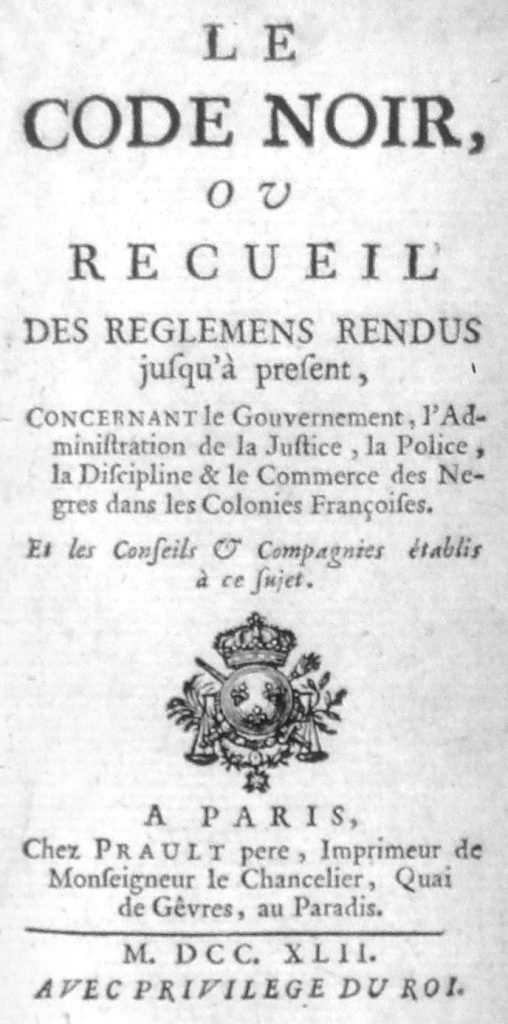

A statue subsequently commissioned privately, which depicted a slave breaking free of chains, was desecrated by detractors. They’d repositioned the chains as shackles and severed an arm, a punishment allowed for escaped slaves under French laws issued in 1685, the Code Noir as it was called. It remained in effect until the French Revolution in 1789.

I don’t know if those responsible for severing the statue’s arm were ever brought to justice but justice of a kind was served. The public mood changed and an appetite grew for Nantes to acknowledge its egregious past.

The approach to the Memorial, opened in 2012 and which I visited today, stretches along a wide path beside the Loire in which two-thousand glass casket-like windows the size of a brick have been placed in the ground, each bearing the name of a slave ship, and some the ports at which they traded their human cargo. They’re positioned randomly and at different angles, much as you might see two-thousand floating ships from a plane.

The sight of so many is immediately effective in demonstrating the enormous scale of the trade. And the names of the ships, often women’s, perhaps of the ship owners’ dearly loved wives and daughters, made me think of how the prevailing norms of the time allowed such dreadful inhumanity to go unseen by those whose lives the trade enriched.

But it’s below deck, when visitors step beneath the sea of names into the underground passage, that the true enormity of the trade’s inhumanity really comes home.

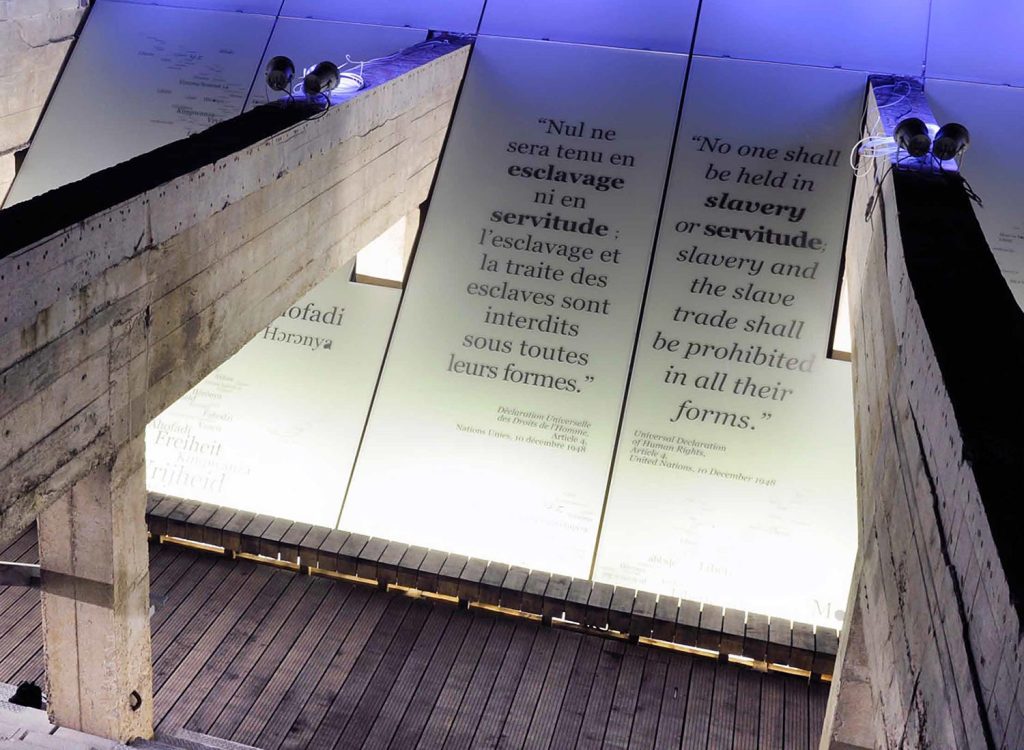

Stepping down you’re immediately confronted by several large glass panels inscribed with key sections of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, a document comprising thirty articles detailing basic rights and fundamental freedoms, inalienable and applicable to all human beings. It’s accompanied by the word ‘freedom’ in the languages of the many countries that endured slavery.

Turning to the left you face a long passage, pictured at the top of this post, and a sense that you’re in the belly of a ship, the dark underbelly into which slaves were packed, chained, underfed and treated with such cruelty that many died at sea, into which, as worthless garbage, they were dropped. The Loire is just visible to the left.

All along the starboard side of the passage are similar glass panels to those greeting visitors when they arrive, stretching ninety metres and inscribed with texts from all four continents touched by the slave trade. One of the most affecting, for me at least, was from a former slave, Olaudah Equiano, who described the stench of the hold as pestilential.

Another was from Captain Louis Mosnier, commander of the French slave ship, Le Soleil, in 1773-1774.

“23rd of March, 1774. They threw themselves into the sea, fourteen black women, all together, all at the same time, in a single motion — what diligence they had, the waves were very large and rough, the winds blowing with torment. The sharks had already eaten many before it was possible to launch a boat so that we could only save seven of them of which one died.”

As immersive experiences go the Mémorial de l’abolition de l’esclavage does well. Climbing out of the passage into a hot and sultry 30c afternoon, complete with rush hour exhaust emissions and the noise of the city, there was a sense of relief, as if coming up for air. There were bowed heads amongst fellow escapees, all white and all silent.

We weren’t responsible but there’s no escaping the fact that we, the great cities in which we live, our countries and our economies, were enriched by the darkness from which we’d just emerged. Though impossible to pay a debt to creditors long gone, it and the enduring impact of the abduction, enslavement and exploitation of millions of Africans surely means that we still owe.